“Desta vez ninguém largou uma bomba sobre nós… Nós montamos a cena, nós cometemos o crime com nossas próprias mãos, nós estamos destruindo nossas próprias terras e nossas próprias vidas” (Haruki Murakami).

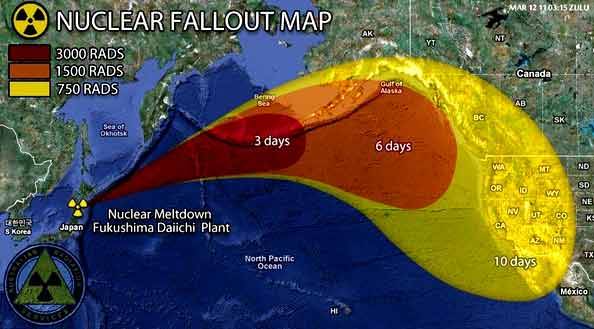

O desastre de Fukushima Daiichi corresponde, como mais de uma vez foi dito, a “uma guerra nuclear sem guerra”. Em 2011, um terremoto no Chile gerou um tsunami que atingiu e causou o derretimento de três dos seis reatores da usina nuclear da TEPCO, situada no litoral leste do Japão, provocando a maior liberação de material radioativo na atmosfera e no mar dos registros históricos e talvez da história do planeta. Já nos primeiros 10 dias após o desastre, em 11 de março de 2011, o transporte pela atmosfera e o depósito (fallout) das partículas radioativas atingiu a costa oeste da América do Norte, como mostra a figura abaixo.

(Veja: http://alternativemediasyndicate.com/2017/02/20/fukushima-contaminated-entire-pacific-ocean-scientists-report/)

Mas a história das consequências de Fukushima estava apenas começando e vai ficando cada vez mais claro, hoje, que elas foram imensamente subestimadas. Na realidade, seis anos após o desastre, não há ainda tecnologia conhecida para descontaminar as instalações, das quais continuam silenciosamente a vazar no mar nada menos que 300 toneladas de material radioativo por dia. Segundo mensurações feitas recentemente na Unidade 2, a radiação era de 530 sieverts, ou 53 mil rems (Roentgen Equivalent for Man), sendo que a dose na qual metade da população exposta morreria é 250 a 500 rems. E é provável que se o robot tivesse conseguido penetrar mais nessa Unidade, o nível de radiação teria sido ainda maior (veja: Helen Caldicott, “The Fukushima nuclear meltdown continues unabated”. Heal Fukushima. Action for Japan and the Earth, 15/II/2017).

Como não há perspectiva de uma diminuição desses níveis letais de radiação e como não há tecnologia à vista para a desmontagem das três unidades atingidas, é lícito se perguntar como o Japão poderá sediar, em 2020, as Olimpíadas. Sobretudo, é lícito se perguntar o que ocorrerá com Fukushima se ocorrer outro terremoto, fato não de todo improvável, haja vista a altíssima propensão a uma intensa atividade sísmica nessa região. Segundo Helen Caldicott, no artigo acima citado:

“Se houver um terremoto maior que 7 na escala Richter, é muito possível que uma ou mais das estruturas de Fukushima colapsem, levando a uma liberação maciça de radiação. Mas as unidades 1, 2 e 3 também contêm piscinas de resfriamento com barras de combustível muito radioativas: 392 na Unidade 1, 615 na Unidade 2 e 566 na Unidade 3. Se um terremoto romper uma piscina, os raios gama seriam tão intensos que o sítio teria que ser evacuado para sempre”.

De qualquer maneira, mesmo que não ocorra outro desastre, o Oceano Pacífico está agora 5 a 10 vezes mais contaminado que nos anos 1946 – 1958, período durante o qual os EUA detonaram 23 bombas atômicas no ar e no mar do Atoll Bikini (Ilhas Marshall), inclusive o chamado Bravo test de 1954 (a detonação atmosférica da bomba termonuclear ou Bomba-H). Isso se reflete naturalmente em toda a fauna marítima, e nomeadamente nos peixes maiores, como mostra o artigo abaixo.

Luiz Marques

Tillamook County, Oregon — Seaborne cesium 134, the so-called “fingerprint of Fukushima,” has been detected on US shores for the first time researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) said this month.

WHOI is a crowd-funded science seawater sampling project, that has been monitoring the radioactive plume making its way across the Pacific to America’s west coast, from the demolished Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in eastern Japan.

The seawater samples were taken from the shores of Tillamook Bay and Gold Beach, and were actually obtained in January and February of 2016 and tested later in the year.

In other strikingly similar news reported last month, researchers at the Fukushima InFORM project in Canada, led by University of Victoria chemical oceanographer Jay Cullen, said they sampled a sockeye salmon from Okanagan Lake in British Columbia that tested positive for cesium 134 as well.

Multiple other reports have circulated online, mostly in alternative media outlets, and mostly not corroborated by any tangible measurement data, that point to cases of possible radioactive contamination of Canadian salmon, but EnviroNews Oregon has not independently confirmed any of these claims.

Testing Fish for Radiation in Sushi Restaurant

Cesium 134 is called the “footprint of Fukushima” because of its fast rate of decay. With a half life of only 2.06 years, there are few other places the dangerous and carcinogenic isotope could have originated.

It is important to note that airborne radioactive fallout from the initial explosion and meltdowns at Fukushima in 2011 reached the US and Canada within days, and circled the globe falling out wherever the currents and precipitation carried it — mostly to places unknown to this day. Even still, radioactive iodine 131 was found in municipal water supplies in places like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts shortly after the initial Fukushima accident — a triple meltdown ranked by EnviroNews USA as the most destructive environmental catastrophe in human history.

The samples from the Oregon coast measured around 0.3 becquerels per cubic meter for cesium 134. Researchers in both the US and Canada said the recently detected radiation levels were extremely low and pose “no risk to humans or the environment.” Sadly, NBC, the New York Post, USA Today, and even The Inquisitr amongst others, took the bait and reported the same thing.

Medical science and epidemiological studies have demonstrated time and again that there is no safe amount of ionizing radiation for a living organism to be subjected to — period. With each subsequent exposure, no matter how small, the subject experiences an increase in cancer risk. In the wake of Fukushima, several governments, and certainly the Japanese government, have raised the “safe” annual limit for radiation exposure for humans — this critics say, to lower legal liability and to placate concerns from the public, in an increasingly radioactive world. Now, many citizens look on in concern, waiting for more testing and data on ocean waters and the seafood they so greatly enjoy.

Você precisa fazer login para comentar.