A nocividade dos pesticidas organofosforados clorpirifós já foi afirmada há quase cinco anos no editorial da revista Environmental Health Perspectives (25/IV/2012). Veja-se: LANDRIGAN, Philip J., LAMBERTINI, Luca, BIRNBAUM, Linda S., “A Research Strategy to Discover the Environmental Causes of Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disabilities” (Editorial). Environmental Health Perspectives, 25/IV/2012.

“Autismo, transtorno do déficit de atenção e hiperatividade (TDAH), retardamento mental, dislexia e outras desordens de base biológica afetam entre 400 mil e 600 mil das 4 milhões de crianças nascidas nos EUA a cada ano. (…) Estudos prospectivos (…) associaram comportamentos autistas com exposições pré-natais a inseticidas organofosforados clorpirifós [inseticidas que inibem a transmissão dos receptores do sistema nervoso] e também com exposições pré-natais a ftalatos. Estudos prospectivos adicionais associaram perda de inteligência (QI), dislexia e TDAH a chumbo, metilmercúrio, inseticidas organoclorados, bifenilos policlorados, arsênio, manganês, hidrocarbonetos aromáticos policíclicos, bisfenol-A, retardantes de chamas brominados e compostos perfluorados. Substâncias químicas tóxicas causam lesões no desenvolvimento do cérebro humano através de toxicidade direta ou de interações com o genoma. Um comitê de especialistas creditados pela Academia Nacional de Ciências (NAS) dos EUA avalia que 3% das desordens neurocomportamentais são diretamente causadas por exposição a substâncias tóxicas no meio ambiente e que outras 25% são causadas por interações entre fatores ambientais, definidos em sentido largo, e susceptibilidades herdadas (National Research Council, 2000)”.

Em 18 de janeiro de 2017, dois dias antes da posse de Donald Trump, a Agência de Proteção Ambiental dos EUA (EPA), agora em vias de ser desmontada por Myron Ebell e Scott Pruitt, publicou um relatório em que declara que dois pesticidas – malation e clorpirifós – afetam 97% das 1.800 espécies listadas como ameaçadas, segundo o Endangered Species Act.

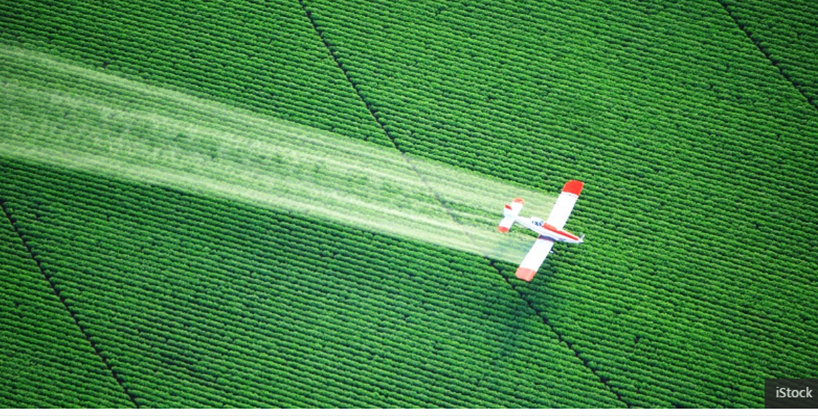

No Brasil, ambos os inseticidas são largamente usados, inclusive com dispersão por aeronaves, malgrado parecer contrário de técnicos do Ministério da Saúde e não obstante a OMS e a Agência Internacional para a Pesquisa do Câncer incluírem o malation entre cinco pesticidas (inclusive o glifosato e diazinon, também usados no país) considerados como cancerígenos. No que se refere especificamente ao malation, ele causa linfomas não-Hodgkin e câncer de próstata. (veja: “OMS classifica cinco pesticidas como cancerígenos prováveis” AFP, 20/III/2015)

Luiz Marques

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released its first rigorous nationwide analysis Wednesday of the effects of pesticides on endangered species, finding that 97 percent of the more than 1,800 animals and plants protected under the Endangered Species Act are likely to be harmed by malathion and chlorpyrifos, two commonly used pesticides. Another 78 percent are likely to be hurt by the pesticide diazinon. The results released Wednesday are the final biological evaluations the EPA completed as part of its examination of the impacts of these pesticides on endangered species.

“We’re now getting a much more complete picture of the risks that pesticides pose to wildlife at the brink of extinction, including birds, frogs, fish and plants,” said Nathan Donley, senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The next step will hopefully be some commonsense measures to help protect them along with our water supplies and public health.”

The three pesticides are all organophosphates, a dangerous old class of insecticides found in 87 percent of human umbilical-cord samples and widely used on crops such as corn, watermelon and wheat. Chlorpyrifos is currently under consideration to be banned for use on food crops in the U.S. The World Health Organization last year announced that malathion and diazinon are probable carcinogens.

“When it comes to pesticides, it’s always best to look before you leap, to understand the risks to people and wildlife before they’re put into use,” said Donley. “The EPA is providing a reasonable assessment of those risks, many of which can be avoided by reducing our reliance on the most toxic, dangerous old pesticides in areas with sensitive wildlife.”

Following these final evaluations from the EPA, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service will issue biological opinions to identify mitigation measures and changes to pesticide use to help ensure that these pesticides will no longer potentially harm any endangered species in the U.S. when used on agricultural crops. As part of a legal settlement with the Center for Biological Diversity, these biological opinions are on deadline to be completed by December 2017.